Meredith Glaser’s job is to quite literally teach the rest of the world how to do urban mobility the Dutch way. Beyond her role as an urban planning researcher at the University of Amsterdam, Glaser leads delegations of politicians, transit agencies and entrepreneurs through the streets of the world’s cycling capital to highlight what infrastructure works and which actionable steps can be brought back to their own cities.

As a global bike boom intensifies in the wake of COVID-19, lessons to be learned from Amsterdam are more important than ever. Just look at the UK’s first-ever Dutch-inspired roundabout in Cambridge. Cities are on their way to introducing hundreds of miles of additional bike lanes and new laws that put two-wheelers first, but there are some significant considerations that must be made in order to embrace a truly equitable and sustainable cycling culture. Here, Glaser explains what they are and how to implement them:

Tell us about your background and why you were drawn to conduct your research in Amsterdam.

After finishing graduate school in California, I was drawn to the Netherlands as an English-speaking region with high sustainability goals. Like me, people from around the world come to Amsterdam to learn about mobility and urban planning, but there was a gap in research when it came to actually implementing change. My PhD in transportation policy and planning through the Urban Cycling Institute puts the focus on how city officials can tangibly achieve what they experience in our city. And what they see in Amsterdam is a place where people bike about 1.2 million miles per day and there are four times the number of bikes than cars on the road. There are approximately 850,000 bikes in this city of 1.1 million people, 60% of whom bike daily. If there’s any city to learn from, this is it.

What are the main takeaways from Amsterdam’s successful cycling model?

There are 40 years of urban planning policy at work in Amsterdam. It really boils down to five main areas.

- Rider safety is a priority.

In a dense urban area like Amsterdam, you can’t have something huge like a car take complete ownership of space (more underground parking facilities are underway in order to free up space in the public realm). Our historic policies around sustainable mobility is to really prioritize safety, to ensure that vulnerable users like pedestrians and cyclists are inherently more safe. Amsterdam’s traffic liability laws uphold that the person who is driving or in the most harmful vehicle is at fault in 99% of crashes. - Amsterdam’s bike network is completely interconnected with the city’s transit system.

Making cycling the gateway to mass transit is a crucial part of a successful bike network. About 50% of all train passengers in our city arrive by bike, and there are creative solutions being implemented to make use of parked two-wheelers. As stay-at-home orders lift in our region and beyond, public transit usage will increase once again and the importance of using micromobility to access it won’t (and shouldn’t) go away. - The city is designed to enable short, slow-speed residential trips.

Most of our roads don’t go beyond 20 mph speed limits. A majority of streets don’t require stop signs, rather there are speed humps and directional signs. Cars yield to cyclists, who in turn yield to the rules of the road. This in turn promotes ridership, which ultimately has an environmental impact as fewer cars (and therefore emissions) are circulating. - The cycling network is continuous and easy to navigate.

Rather than have intermittent pop-up bike lanes that come to a halt, Amsterdam has a connected bike network that spans the length of more than 475 miles. While of course this is difficult for cities to build at such later stages of urban planning, the ability to make paths feed into one another should be prioritized in order to keep riders safe and infrastructure contained. - Equitable mobility is a must.

Inclusivity reigns supreme in Amsterdam, where access to bikes, whether its personal usage or in the sharing form, is prioritized. Since so many people own and regularly use their bikes, traditional perceptions related to race, ethnicity, gender and economic status are lessened here. Now more than ever, there are more opportunities for mayors, officials and urban designers to learn how to build a support network for underserved communities.

What are initial steps city planners and other stakeholders can take to make changes?

New York or San Francisco will never be Amsterdam. The leaders that come to learn from our streets know this, but the point is to replicate some basic and key factors given each city’s own circumstances. Eliminating car dominance is the optimal goal, but getting there may look differently. I hope that cities implementing the courageous measure of opening new pop-up bike routes have a chance to actually learn from the lanes themselves. Learning requires fostering relationships, communication, resources and leadership. We know from crisis research that the recovery period is a special time where decision-makers can be really open-minded. We have a once-in-a-lifetime chance to learn from our collective history of auto dependency and build something better.

How has city cycling infrastructure changed worldwide in the face of the pandemic?

It almost happened overnight, traffic suddenly gone. I’m very impressed with how cities have managed to react so quickly and during stay-at-home measures no less. City staffers are at home themselves and building bike lanes and slow streets at rapid rates, and all the while dealing with public health issues. A lot of cities are doing a great job communicating the benefits of these programs in a short period of time. In Chicago, for example, the city’s slow streets have taken a much more economic focus, where there’s a clear emphasis on restaurants and expanding sidewalks so they can put diners on the streets rather than parked cars. Cities have been forced to reconsider streets as public spaces, where pedestrians, bicycles, electric scooters and other micromobility vehicles are being prioritized for the first time.

Which other global cities have sustainable models worth replicating?

Outside of the Netherlands, Copenhagen is our friendly bike rival. (See the Copenhagen Index to get an idea of which cities are making headway.) Munich has introduced a successful marketing campaign to encourage cycling that is paying off, while Bordeaux and Dublin are really emerging cycling cities. In Seville, Spanish city planners seized their own moment of opportunity and implemented a public referendum to build a network of bike facilities in 2018. It was built in 18 months and saw cycling trips increase from 0% to 9%. These places are all setting examples for the world to see at this transformative time.

At the intersection of tech and urban planning, where are we going next?

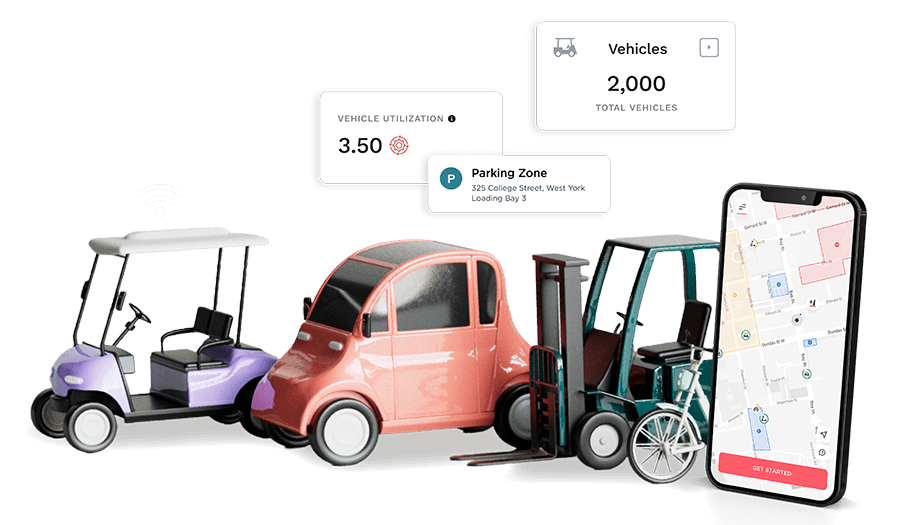

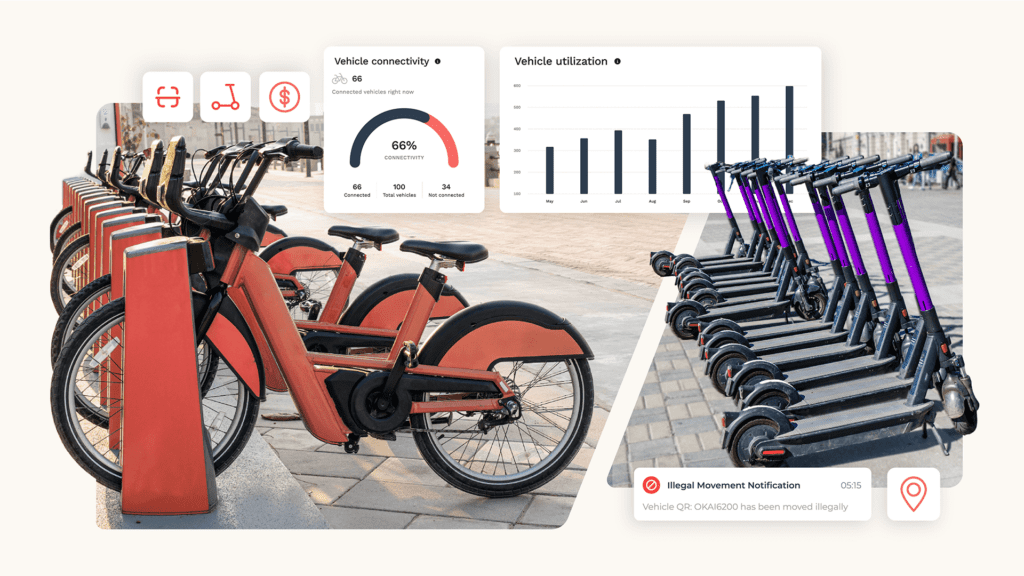

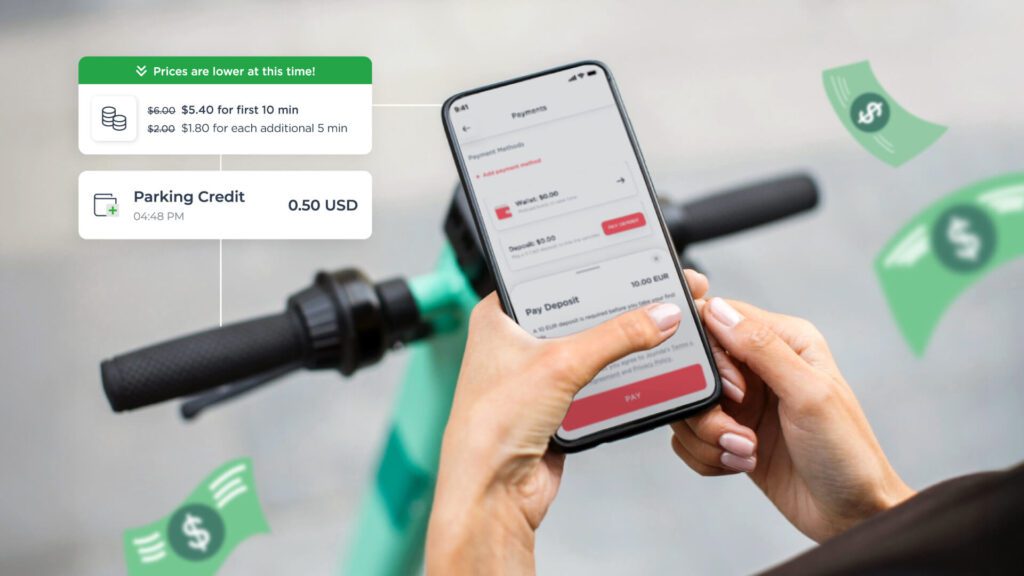

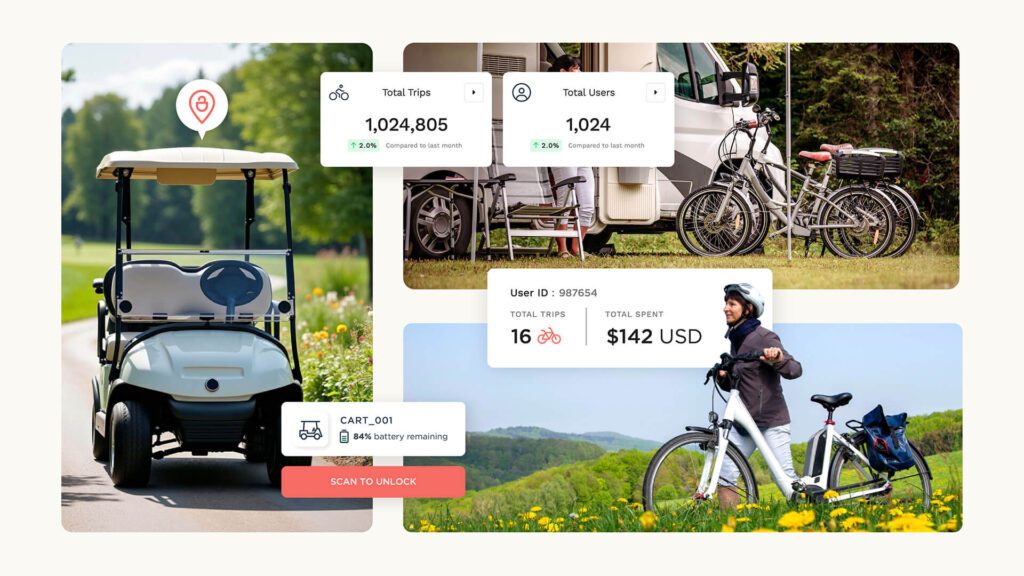

To me, the underrepresented theme in transport is seeing city streets themselves as evolving technology. And as a software provider, Joyride understands that tech relies on engagement. Streets across the globe were coded more than 100 years ago to satisfy one user—a car. To continue the metaphor, tangible tech in the form of shared mobility is now getting people from place to place in efficient ways that still must fit in with old tech. The pandemic has highlighted this relationship between shared systems, MaaS, ride-haling and cars, and I think we’re all learning to adapt better and embrace change because there’s no other choice. While e-scooters are still banned in Amsterdam, the whole sharing economy and MaaS sector have taken off as we think of new ways to incorporate these technologies. The dynamics of rapidly changing technology, engagement and associated behaviors are making us think about how we can build streets that better accommodate a present and future that’s beyond the automobile.

To learn more about how Joyride works closely with cities to implement sustainable shared mobility systems, contact us today.